Our high-tech world runs on some unsung chemical heroes. Compounds like vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅), sodium metavanadate (NaVO₃), tantalum and niobium chlorides (TaCl₅, NbCl₅), tungsten hexachloride (WCl₆), and molybdenum pentachloride (MoCl₅) might be unknown to most people, but they do vital work behind the scenes. These materials are often found in tiny amounts inside batteries, electronics, catalysts, and specialty materials – the hidden ingredients that make things go. Think of them as secret spices in a recipe: each one adds a special property that makes devices safer, faster, or more efficient. In this article we’ll explore what these compounds are and why they matter in everyday technology, from energy storage to smartphones.

Vanadium Compounds: Catalysts and Energy Workhorses

Vanadium compounds are chemical multitaskers. Vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) is a bright yellow-orange solid that’s best known as an industrial catalyst. For example, it’s the key ingredient in the contact process that makes sulfuric acid – one of the world’s most widely used chemicals. V₂O₅ also appears in the exhaust systems of power plants and trucks (as part of “selective catalytic reduction” systems) to clean up pollution. In each case, vanadium’s chemistry helps speed up important reactions without being consumed. Besides catalysts, V₂O₅ is used in special glasses and ceramics – it can give glazes a golden shine or be part of heat-resistant coatings. And in recent years, vanadium became famous for batteries: vanadium redox flow batteries use vanadium ions (often derived from V₂O₅) dissolved in liquid. These huge batteries can store renewable energy on the grid, and vanadium’s ability to cycle between several oxidation states (+4, +5, +3, etc.) makes it perfect for this job.

Even related vanadium salts play their own roles. Sodium metavanadate (NaVO₃) and ammonium metavanadate (NH₄VO₃) are water-soluble vanadium salts. They’re often used as precursors to make other vanadium materials. For instance, scientists dissolve vanadium ores and add sodium or ammonium to pull the vanadium into solution as NaVO₃ or NH₄VO₃. Then, by heating or chemical reaction, these salts can be converted to V₂O₅ or other vanadium oxides. In other words, NaVO₃ and NH₄VO₃ are like vanadium “intermediates” in manufacturing processes. They also find niche uses: for example, making thin vanadium oxide films for electronics or sensors, and acting as corrosion inhibitors in specialty coatings. Altogether, vanadium compounds (from V₂O₅ to metavanadates) stand out for roles in catalysis, energy storage, and materials processing.

Tantalum and Niobium: Electronics Enablers

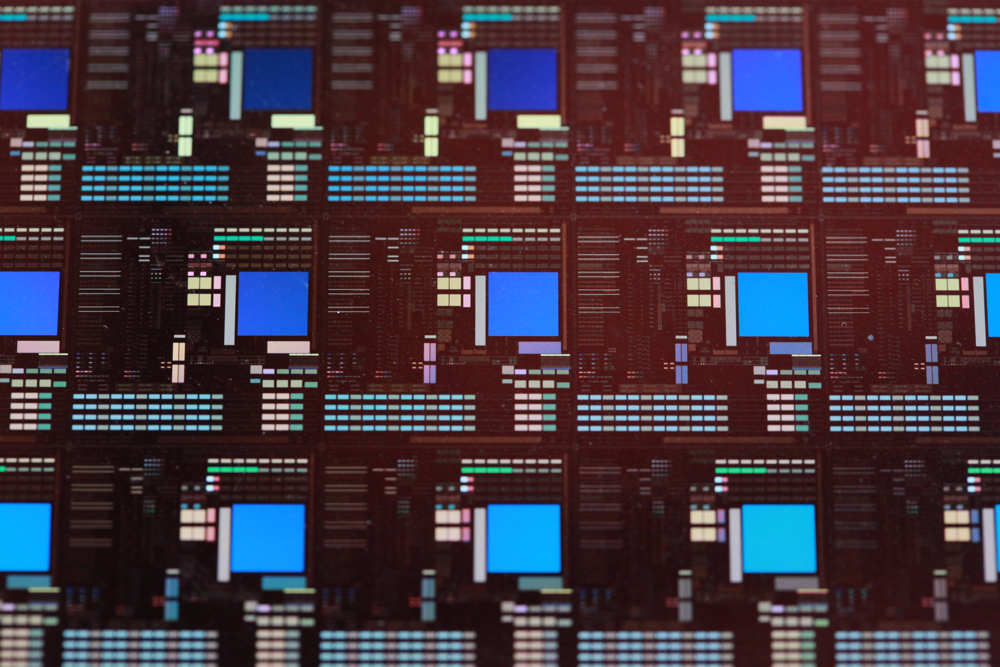

A silicon wafer patterned with millions of tiny microchips illustrates the scale of modern electronics. Compounds like niobium pentachloride (NbCl₅) and tantalum pentachloride (TaCl₅) are used to lay down the ultra-thin layers of metal that make these chips work.

The group-5 metals tantalum and niobium are behind many electronic devices. They are extremely corrosion-resistant and have special electrical properties that engineers love. Tantalum pentachloride (TaCl₅) and niobium pentachloride (NbCl₅) are volatile, reactive compounds used mainly as precursors to deposit tantalum and niobium in thin films and ceramics. For example, in making multi-layer ceramic capacitors (the tiny capacitors inside smartphones and computers), engineers often use Ta or Nb compounds in a vapor deposition process so that ultra-pure tantalum or niobium oxide forms inside the device. These capacitors are prized for being small yet holding more charge than aluminum capacitors. In fact, many of the capacitors on a cellphone’s circuit board contain tantalum (and increasingly niobium) because of their reliability.

Beyond capacitors, TaCl₅ and NbCl₅ enable other cutting-edge manufacturing. They can be used in Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) or Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) to coat wafers with tantalum nitride or niobium compounds. This is how we put down uniform metal layers for resistors, transistors, and even tiny superconducting wires in advanced chips. For instance, niobium compounds are vital in making superconducting qubits for quantum computers (niobium being a superconducting metal). Tantalum likewise is added to alloys for jet engine parts because TaCl₅ can produce pure tantalum that resists heat. You might even find tantalum and niobium in medical implants and prosthetics – their compounds are biocompatible and corrosion-proof.

So while TaCl₅ and NbCl₅ sound exotic, their role is simple: they deliver precious metals exactly where engineers need them, in just the right way. They are the “paint” for building technology’s finest electronics. Without these chemicals, our devices would either fail (less reliable capacitors) or be bulkier (more aluminum instead of tantalum). Tantalum and niobium compounds quietly make our portable electronics more powerful and robust.

Tungsten and Molybdenum: The Tough Catalysts and Metals

A glowing tungsten filament (in a vintage lightbulb) reminds us that tungsten metal is very heat-resistant. Tungsten chloride (WCl₆) shares this property in a chemical sense: it can be used to deposit tungsten in high-tech processes like chip manufacturing.

Tungsten and molybdenum are heavy-duty transition metals with chemistry that helps in extreme environments. Tungsten hexachloride (WCl₆) and molybdenum pentachloride (MoCl₅) are both volatile, chlorine-containing forms of these metals. They are mostly used as precursors for catalysts and coatings. For example, WCl₆ can be used in solutions or vapor to produce tungsten metal or tungsten carbide. In industry it’s a building block for making hard materials like cutting tools, but more intriguingly it’s used in organic chemistry for polymerization catalysts (like olefin polymerization to make plastics) and in electronics. In semiconductor fabs, WCl₆ or its derivatives are used in processes like Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) to coat microchips with tungsten layers. This is important because tungsten has very low electrical resistance and high melting point, making it ideal for connecting parts of a chip or for certain transistors. Likewise, MoCl₅ is a chemical tool for making molybdenum-based materials. It can produce molybdenum oxides or sulfides that serve as catalysts, and it’s also a precursor for electronic materials.

Even outside chemistry labs, tungsten and molybdenum lend strength. Pure tungsten metal is famous for lightbulb filaments and rocket engine nozzles because it stays solid at extreme heat. Molybdenum strengthens steel in aircraft engines. But their chlorides have more subtle roles: they are like stencils or masks in manufacturing, precisely delivering the metal or oxide only where needed. One analogy: tungsten hexachloride and molybdenum pentachloride are to tungsten and molybdenum what liquid titanium is to titanium metal – they let us use the metal in ways that raw powder wouldn’t allow.

In emerging technologies, molybdenum compounds also play into new batteries and catalysts. For instance, molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) is studied as a lubricant and in batteries, and MoCl₅ is a stepping stone to making it. Tungsten oxide (WO₃) and vanadium oxide (V₂O₅) are both used in “smart windows” and gas sensors. All in all, WCl₆ and MoCl₅ underlie many processes that produce everyday materials – from computer chips to car parts.

Energy Storage and Catalysis: Key Roles

A common thread among these compounds is energy and chemistry catalysis. Vanadium and niobium compounds are both important in energy storage: vanadium in flow batteries, niobium in advanced lithium-ion batteries or supercapacitors (Nb₂O₅ anodes and LiNbO₃ electrolytes are studied for fast charging). Tungsten and molybdenum materials (like tungstates and molybdates) appear in high-capacity battery electrodes and fuel cells too. In catalysis, all of these metals show up. Vanadium oxide catalysts purify exhaust and make acids; tungsten and molybdenum chlorides initiate polymer chemistry; tantalum and niobium oxides catalyze photo-oxidation and water splitting.

Think of a catalytic chemical plant or battery factory as a big kitchen. These rare compounds are the ingredients that make the reaction recipe work efficiently. Just as a dash of spice can transform a dish, adding trace amounts of these metals or their compounds can dramatically increase performance or yield. For example, adding a tiny percentage of niobium or tantalum to aluminum or titanium alloys makes jet engine components last longer. Doping glass with molybdenum oxides can change its color or conductivity. These are specialty uses, but they tell a clear story: tiny amounts, huge impact.

Connecting the Rare Elements

What ties these compounds together is their position in the periodic table and their chemical behavior. Vanadium, niobium, and tantalum are in Group 5, so they often share oxidation states (+5) and bonding types; similarly, tungsten and molybdenum are Group 6 and can mimic each other. For instance, NbCl₅ and TaCl₅ are nearly interchangeable in certain chemistry labs. Vanadium pentoxide (a +5 oxide) can sometimes substitute for niobium pentoxide in ceramics. This means knowledge from one system often carries over to another, allowing technology to adapt.

They also share the theme of processing difficulty: many are expensive to extract and refine, which is why we don’t see large quantities of them in raw form, but rather in specialized compounds. That rarity is part of their appeal: a “rare earth” isn’t common, but as long as we make the most of every atom, we get great performance. Recycling and careful design aim to keep these valuable materials in use rather than waste them.

One analogy is to think of these compounds as precision tools in a toolbox. We don’t need a chainsaw for every job, but when we do, nothing else works as well. Likewise, we don’t put vanadium pentoxide in every factory, but for the jobs it does, there’s no substitute. In battery terms, we might use cheaper manganese or iron in some designs, but vanadium’s unique chemistry makes flow batteries possible at large scales. For microchips, copper and aluminum cover most wiring, but at the tiniest features, tungsten or niobium films made from WCl₆ or NbCl₅ might be required for reliability.

Conclusion

Many cutting-edge devices and industrial processes rely on these rare compounds. From V₂O₅ in factories and batteries to TaCl₅ and NbCl₅ in your smartphone’s internals, to WCl₆ and MoCl₅ in the machines that make everyday materials – they are the hidden foundations of modern tech. Next time you flip on a light or tap your phone, remember that beyond silicon and lithium, there’s a cast of lesser-known chemicals enabling that technology. They may sound obscure, but vanadium, tantalum, tungsten, molybdenum and niobium compounds quietly work behind the scenes. By shaping chemical reactions and material properties, they help power our world – one tiny molecule at a time.